|

Date: Organization: Summary: Author: |

22 November, 2024 Encore, Cheyenne, Wyoming A select sampling of virtual reality technologies the evolved over the years. Tim Munyon, M.A., B.S. – Developing and delivering training solutions for 30 years. |

Definitions

- Augmented Reality (AR) – A partially-immersive environment in which the headset allows users to see their actual surroundings, but the headset adds digital elements to it. For example, users see the room around them, but the headset might add digital shelves, tables, or other interactive elements to the room.

- Extended Reality (XR) – An umbrella term that encompasses both AR and VR.

- Virtual Reality (VR) – A completely immersive environment in which the headset blocks out all external stimuli and provides 100% of the simulated reality users see. Headset users might be digitally experiencing a roller coaster ride, engaged in battle, exploring historical landmarks, or performing surgery.

Historical Origins – Select Examples

If you or a family member are considering taking training where you play a game or develop job skills while wearing a virtual reality headset, there is nothing to be afraid of. Inventors have been working on ways to provide people with a more immersive visual or auditory experience for over 150 years!

Oliver Wendell Holmes created a stereoscope in 1861 that allowed users to see images in 3-D. He called his invention the “hand stereopticon.” Users would insert a “stereoview” card with a right and left image in the target end of the device, then view it with a lens that focuses each individual eye on its corresponding image (Jack).

The two images would be taken by a camera from the same focal point, but at different angles, similar to how the human eye provides two different images to the brain, which processes the images into one 3-D perception of the world.

To safely train airplane pilots how to fly “blind” (by instruments alone), Edwin Link created a flight simulator cockpit, called the Link Trainer, in 1929. Pilots could sit inside a closed cockpit, see the instrument panel, and interact with the controls. Soon commercial airlines were training pilots with the Link Trainer, and the U.S. government purchased them during World War 2 to train new military pilots (Britannica 2018, 2023; photo from Naval Air Station).

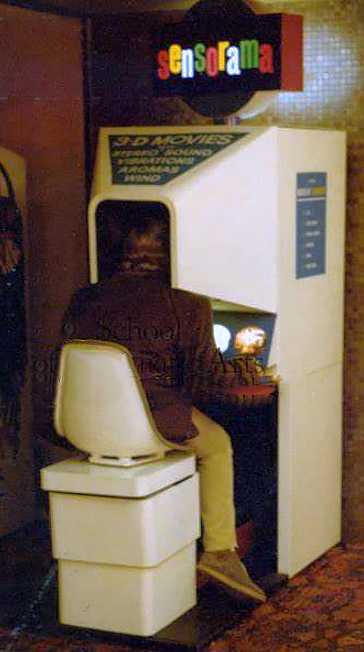

In 1962 cinematographer Morton Heilig patented one of the earliest attempts at an immersive video experience. Heilig would first create short movies with a bulky 3-lens camera. The heavy camera apparatus, which captured multiple recordings from slightly different perspectives on 35mm film, was necessary to project a stereoscopic display for the viewer. Each eye of the person viewing the film would receive a projection from a slightly different angle.

Viewers would sit on a chair and place their heads into the cowling of an arcade-like console called the Sensorama. He created a larger booth that would accommodate four viewers at a time. The Sensorama provided 3-D images, a wide-angle view, stereo sound, scent-emitters, fans for air movement, and vibrations (Sakane). As viewers watched the recording, they would experience all of the sensory effects that were synchronized to the events in the film. For example, someone riding a motorcycle through New York City would smell exhaust fumes from other vehicles, hear traffic sounds, feel the vibrations of the seat, and have the wind blowing in their faces. (Photos from immersivearchive.org.) Heilig produced 5 short films, including Motorcycle and Dune Buggy, and then took the Sensorama on a nation-wide tour. Unfortunately, he never succeeded in finding a wealthy investor who could fund the transition of his invention prototypes to a commercially available product.

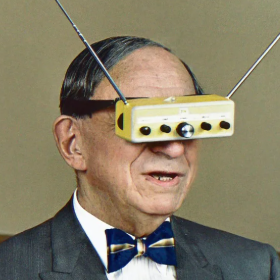

The following year, 1963, inventor Hugo Gernsback created 3-D TV eyeglasses called “teleyeglasses” (Ackerman). In the headset, each eye would view its own 1″ square cathode-ray TV tube, which provided the 3-D view. His invention looked eerily similar to modern VR headsets, but with the addition of the telescoping TV antennas in use at the time. The pocket-sized teleyeglasses weight about 5 ounces and ran on low-voltage current provided by batteries. Gernsback’s teleyeglasses never went into production, due to manufacturing costs and the resulting cost to the consumer. (Photo from Folli.)

Roman philosopher Cicero popularized a moral parable in his 45 B.C. book, “Tusculan Disputations.” The parable illustrates how those in power live their lives under the specter of anxiety and death (Andrews). The tyrant in the parable, Damocles, had to sleep in a bed with a sword (the Sword of Damocles) suspended from the ceiling directly over his resting place.

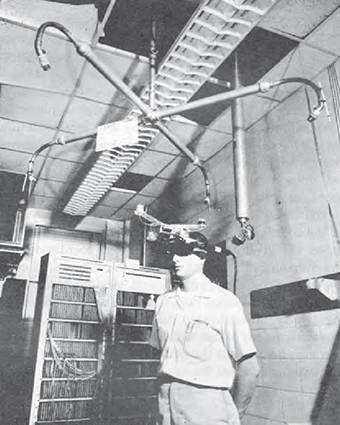

In 1968 a device called the “Stereoscopic-Television Apparatus for Individual Use,” nicknamed the Sword of Damocles, was created by Ivan Sutherland with the help of his student, Bob Sproull, at the University of Utah. This time the “sword” consisted of tubular VR headset apparatus suspended from the ceiling, with head-movement sensors hanging from an overhead X-shaped support structure.

The headset would display left and right output from a computer program that adapted in real time to the head movements of the wearer. The images consisted of wire-frame 3D environments. Videos are available on the Internet that show the cumbersome headset being worn by Sutherland (e.g., Walkden; photo from Gupta). Sutherland’s invention was an early example of what is today called a “head-mounted display.”

VR as a virtual reality exposure therapy tool for PTSD started in 1997, when Georgia Tech, Emory University, and the VA hospital in Atlanta started testing the Virtual Vietnam VR intervention with veterans diagnosed with PTSD (Reist; photo from Pair). The hardware included a head-mounted display (HMD), high-quality stero earphones, a position tracker, and a vibrating seat.

One Virtual Vietnam environment simulates a ride in a helicopter during combat operations. The HMD provided the visual surroundings, the earphones provided the sounds of helicopters, gunfire, and explosions in directional stereo, and the seat provided the vibrations of a helicopter in flight. The VR program provides a way for the participant to experience visual, auditory, and tactile input in a simulation that immerses them with a safe, controlled environment where they can learn how to understand and control their responses.

The results of the intervention were positive. Kandalaft, the leader of the study, stated, “Significant increases on social cognitive measures of theory of mind and emotion recognition, as well as in real life social and occupational functioning were found post-training” (Kandalaft).

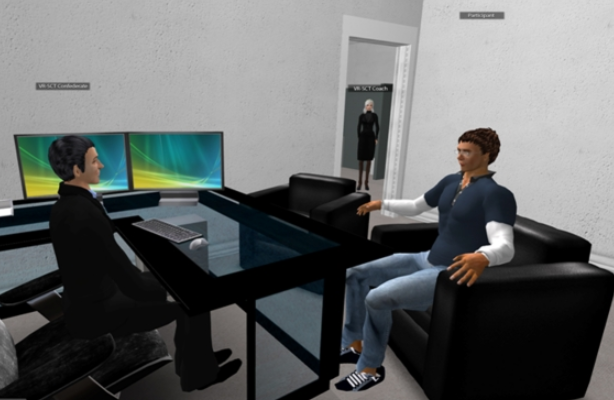

Scenarios could be set up so that the participants (interviewee in the chair) are questioned by the participating therapist (interviewer in the chair), and the coach therapist (doorway) observes and provides feedback (caption and photo from Kandalaft).

Conclusion

If you or a family member will be taking virtual reality training, be assured that it will be a safe and rewarding experience. Various attempts at some form of 3-D immersion have been around for decades. VR programs designed specifically to help veterans with PTSD were being used over 20 years ago!

Today, VR technology has developed to the point where participants can interact with objects using their own hands—battery-powered controllers for each hand are no longer required. VR currently provides learning opportunities over a wide range of social, physical, communication, financial, and daily living skills.

For more information on how VR is helping people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, refer to the other articles Encore recommends on www.encoresvs.org.

References

Ackerman, Evan. “The Man Who Invented VR Googles 50 Years Too Soon.” IEEE Spectrum, 30 November 2016.

Allnutt, Richard Mallory. Link C-3 Flight Training – Restoration Update. Military Aviation Museum, 07 October 2024.

Andrews, Evan. “What was the sword of Damocles?” History, 10 August 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “flight simulator”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 9 Nov. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/technology/flight-simulator. Accessed 23 October 2024.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Link Trainer”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 May. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/technology/Link-Trainer. Accessed 23 October 2024.

Folli, Lorenzo. “Lorenzo Folli, History in Color.” Instagram.

Fupta, Pankaj. “Virtual Reality: A Journey into a New Digital World.” Theinvisiblenarad.com, 14 October 2023. https://theinvisiblenarad.com/virtual-reality/

Immersive Archive, “The Sensorama.” Immersive Archive, n.d.

Jack, Emily. Artifact of the month: Holmes Stereoscope. NC Miscellany, UNC, 21 October 2013.

Kandalaft MR, Didehbani N, Krawczyk DC, Allen TT, Chapman SB. “Virtual reality social cognition training for young adults with high-functioning autism.” J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Jan;43(1):34-44. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1544-6. PMID: 22570145; PMCID: PMC3536992.

Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale Museum. The Link Trainer Flight Simulator.”

Pair, Jarrell. “’Virtual Vietnam’ PTSD Therapy System (1997-1998).” (Not a secure website.)

Reist, Christopher. (2015). Virtual Reality Exposure for PTSD Due to Military Combat and Terrorist Attacks. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 45. 10.1007/s10879-015-9306-3.

Sakane, Itsuo. “Morton Heilig’s Sensorama (Interview).” January 5, 2011. Educational video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vSINEBZNCks&t=1s

Walkden, Gary (Immersed Robot). “Retro VR #1 // Ivan Sutherland and the Sword of Damocles.” December 18, 2020. Educational video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFqXGxKsM3w